Inside Angle

From 3M Health Information Systems

Tackling health care’s ever-decreasing competition

In a recent perspective piece in JAMA Forum, Dr. Ashish Jha of the Harvard School of Public Health argues that increased provider consolidation is threatening the financial viability of the U.S. healthcare system. From his point of view, the future of the system is predicated upon patient selection of independent providers, as well as competition. While an excellent overview of troubling market changes, we would suggest that there are three additional features that warrant consideration when discussing the healthcare landscape:

- Emerging vertical consolidation of hospital systems that are becoming insurers within narrow geographic regions,

- The transparent marketplace created under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that enables provider- led plans to connect directly with employer groups, and

- The “insurer fee” that pushes ever more employer groups to “self-insure.”

This blog examines these trends, in general, and reviews how they are playing out in one state: Pennsylvania. We also discuss the effect consolidation is having on the actions of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the need for this agency to find another path to regulate the market.

Provider-led health plans have been growing since passage of the ACA in 2010. A report by McKinsey, published in April 2016, plotted out a typical pathway for provider groups to launch their own health plan start-ups. Typically, according to this report, they start with Medicaid managed care, expand to Medicare Advantage and finally launch on the health insurance exchange. There are very good reasons for this trajectory.

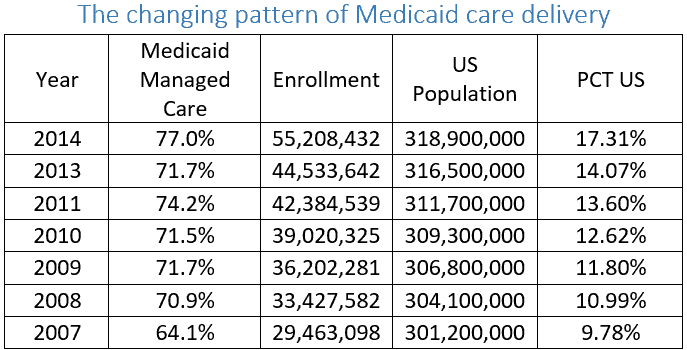

First, Medicaid programs increased their reliance on managed care at the same time that Medicaid coverage increased. In 2014, over 17 percent of the U.S. population was enrolled in a Medicaid managed care plan – nearly double the number from seven years previously. Medicaid programs are not renowned for generous payments. Hence, provider organizations prefer to assume managed care risk (capitation) and not deal with insurers.

Source:

Medicaid Data: Kaiser Family Foundation; Population data: Google Public Data

Second, similar forces are driving providers toward establishing Medicare Advantage plans. Considering the complexity of CMS Value-Based Purchasing and the increasing presence of alternative payment models (APMs) encouraged under MACRA, providers realize that establishing a self-sponsored Medicare Advantage plan will yield greater rewards and stability than establishing an Accountable Care Organization ACO. According to research conducted by Avalere Health, 60 percent of new Medicare Advantage plans are sponsored by healthcare providers. Medicare Advantage enrollment in 2016 is estimated at 17.6 million Medicare enrollees (31 percent of total Medicare enrollment).

Third, a major game changer, is the transparent marketplace created under the ACA. On the health insurance exchange there is no hiding higher cost by varying patient liabilities or covered benefits. Insurance costs are clearly labelled for all to see when purchasing. The exchange also enables smaller, newer, provider-led plans to connect directly with employer groups without establishing relationships with brokers. Moreover, the posted prices for exchange products act as a prominent advertisement of relative costliness for off-exchange insurance products. A reasonable employer group can expect that if a provider plan offered by a particular health system is cheaper for an on-exchange product then that should hold for other offerings. The ACA has also, maybe more importantly, pushed employer groups to both become self-insured (which requires Administrative Services Only) to avoid the “insurer fee” and, thereafter, demand more effective mechanisms to manage population health. If you want population health managed, who better than the local health system?

While ahead of the curve, Pennsylvania has become an unfolding battleground as the traditional dominant health system in the west of the state, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) and the dominant insurer, Highmark, one time partners, have integrated vertically – but not with each other. Recently UPMC purchased Susquehanna Health moving the competition between UPMC and Highmark, which had been playing out in the Western part of the state, to the Central region. Geisinger, a nationally-recognized poster child for provider-sponsored health plans in the Central region, is busy expanding its own insurance operation and clinical partnerships further east. Against this backdrop of integration and consolidation it is almost surprising that the proposed merger of Penn State Hershey Medical Center and PinnacleHealth in central Pennsylvania was temporarily blocked by the FTC1. The pace of consolidation is making FTC regulation impossible outside of select cases, which are only taken on if the agency has a very high probability of winning.

Pennsylvania may be atypical in the number and market share of provider-led health plans. According to the same McKinsey report, as of 2014, PA covered 1.9 million enrollees within provider-led health plans (a number closely followed by MI, NY & TX). But the expansion of provider plans with attendant complexity is not confined to those states.

The FTC addressed these same issues in the proposed merger between Chicago-based Advocate Health Care and Northshore University Health System. Northshore is a new entity emerging from the earlier Evanston Northwestern Healthcare Corporation merger, which itself was challenged by the FTC[i]. A notable shift in the Evanston case was that the ruling changed the way in which monopoly power was to be determined in health care – namely to focus on the effect provider consolidation has on reimbursement rates negotiated by insurers2. The latest win for the FTC in the Advocate case temporarily blocks the merger. However, it has introduced a new problem and left an old one unresolved. In the Evanston decision, the FTC committed itself, in future merger evaluations, to balance potential quality gains with the adverse effects of a monopolistic market structure3. The ability to define quality gains pre-merger was noted as a potential weakness for future cases and not fully addressed in the Advocate victory. The new dimension, brought forward in defense of the proposed Advocate/Northshore merger, is the merger’s stated intent to pool resources to create a new insurance product that would decrease insurance premiums by at least 10 percent. This new insurance product would directly compete with the dominant Blue Cross product.

To consider both improved quality and the effect that a hospital merger has on insurance rates, the FTC now has to:

- assess the anti-competitive effects of health system consolidation on insurance premiums for existing insurers;

- quantify potential gains from quality improvement;

- project the potential effects on the regional insurance market of adding a competitive alternative; and

- assess the potential for anti-competitive impacts due to adding a product in the downstream insurance market sponsored by an upstream monopoly.

The net of these considerations is to take an already complex series of relationships and make modelling them almost impenetrable. It is far from clear how to achieve the optimal outcome– the market structure that returns consumers the greatest long-term benefit in terms of lower costs and higher quality – and how a court can be educated as to what it looks like. Hence, the need for the FTC to find an alternative approach that provides a cautious pathway that can deliver improvements without years of litigation.

When the FTC first intervened, the Advocate and Northshore Health Systems offered to give price undertakings – guarantees of their future conduct and performance – as a means to head off extensive litigation. In previous blogs we have proposed development of a regulatory framework that provides guardrails of cost and quality outcomes to serve as the basis of undertakings given by the merging parties and administered (with penalties) by regulators. The pace of change means that we have to specify quality and cost metrics that should be the foundation for any evaluation of new market structures. So, why not set the quality and cost standards up front? Why not pay for improved outcomes?

Richard Fuller, MS, is an economist with 3M Clinical and Economic Research.

Norbert Goldfield, MD, is medical director for 3M Clinical and Economic Research.

References

- Catellucci M. Federal tab for insurance subsidies may boost scrutiny of provider competition. Mod Healthc. 2016.

- Pak C, Cauley K. FTC v. Evanston: Antitrust Enforcement of Hospital Mergers Receives a Shot in the Arm. J Health Life Sci Law. 2008.

- Ramirez E. Antitrust enforcement in health care–controlling costs, improving quality. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(24):2245-2247. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1408009.

[i] In their winning argument, the FTC provided a framework that moved away from patient flow tests (A.K.A. Elzinga-Hogarty geographic market definition test) and focused more on the reality of health care using a “hypothetical monopolist test”. A detailed summary of the case can be found in “Evanston’s Legacy: A Prescription for Addressing Two-Stage Competition in Hospital Merger Antitrust Analysis”