Inside Angle

From 3M Health Information Systems

Meaningful outcomes comparison requires risk adjustment, but the risk adjustment needs to achieve its purpose

Risk adjustment is a correction applied in hospital performance measurement to account for the contribution of population characteristics that are beyond the control of the hospital. The effects of these characteristics are not considered to be the responsibility of those being measured, yet impact the assessment of good and bad performance. If we select a target outcome, for example hospital mortality, we risk adjust for patient characteristics (e.g. patient illness burden and the nature of admission) that otherwise obscure comparisons of relative hospital performance. As set out in our blog post from May last year, a great deal of care needs to be taken with how we define the target outcome for measures like mortality, as well as how we define the accompanying risk adjustment model when making comparisons across providers of relative outcomes performance. More recently our blog turned to the ongoing (and long running) discussion of the structure within which a socioeconomic status (SES) adjustment may be added to the risk adjustment of hospital performance under the hospital readmission reduction program (HRRP).

These blogs capture two central aspects of risk adjustment in performance measurement. First, the target outcome needs to be clearly defined both for what is included and what is excluded, so as to best reflect the concept being measured. Second, factors that are known to impact the performance measure (e.g. SES) need to be argued for inclusion or exclusion by assessing their respective merits. In the case of hospital mortality rate measures conducted by CMS, we argue that “preventable” mortality is the concept that should be pursued while developers often believe that all-cause mortality1 is an appropriate substitute outcome, permitted by the use of a robust risk-adjustment model. For readmissions, strong arguments have been put forward by both proponents and opponents of a SES adjustment centered on the responsibility of hospitals to mitigate adverse outcomes that result from variation in patient SES.

What makes these two examples stand out is the considerable attention applied to the structure of the risk adjustment model and the detailed examination of the pros and cons of their approach. In our recent article published in the American Journal of Medical Quality2 we highlight the highly limited and little discussed risk adjustment models employed by the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) when measuring standardized infection ratios (SIR)3. In the SIR guide it is stated that:

“The SIR adjusts for various facility and/or patient-level factors that contribute to HAI risk within each facility.”

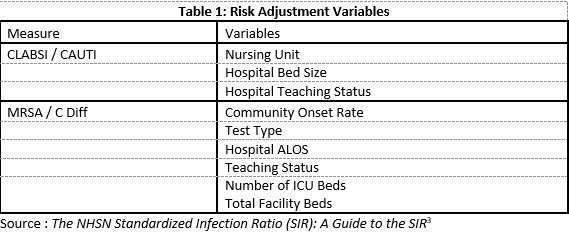

In Table 1 we summarize what the “patient-level factors” mean in practice for risk adjusting infection rates for acute general hospitals.

Table 1 reports four “patient-level” risk adjustment factors, comprising a hospital reported description of nursing unit, a count of total facility beds, hospital reported teaching status, a facility ALOS reported in AHA statistics, and a community onset rate of infection. These elements form the basis of risk adjustment for the measures included in the Value-Based Purchasing Program (VBP), and the Hospital Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP). All have been endorsed by the NQF and are responsible for billions of dollars of payment transfers across hospitals.

It is very hard to identify which variables serve as “patient-level” risk factors in the risk adjustment model (unless we count the hospital designation of “unit type” where the patient was treated). Our article points out that there are many questionable aspects of the SIR methodology. These include the risk adjustment variables that have been selected (and those omitted), the published statistical results and stability of coefficients, the dependence upon hospital self-reported data to determine quality (and thereby penalties) and the focus upon an outcome such as infection per central line day when a major intervention is to reduce the number of days. In short, we see plenty to dislike in the models.

But what is particularly troubling is the general acceptance of a risk adjustment method that is so far removed from addressing patient-level risk. NHSN SIR ratios are not just found within the VBP and HACRP programs, but also the Hospital Compare Stars ranking used to steer patients towards higher quality facilities. In a recent article, David Nerenz et al considered the inappropriate weighting of quality domains within the hospital star rating program4. Their analysis focused on the complex algorithm (latent variable modeling) that CMS employs to “load” quality measures onto a single quality “dimension” to provide a guide point for hospital quality. They go on to conclude that the current loading has resulted in a biased summary measure with the potential to mislead patients. If the component measures are themselves seriously flawed, as we believe, then evaluating hospitals by their relative (attainment) and improvement scores in everything from VBP to Hospital Compare Stars faces more problems than how they are summed.

Richard Fuller, MS, is an economist with 3M Clinical and Economic Research.

References

- Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation (YNHHSC/CORE). 2019 Condition-Specific Mortality Measures Updates and Specifications Report.; 2019. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228890945322&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3D2019_Condtn-Spec_Mort_AUS_Rpt.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs.

- Fuller RL, Hughes JS, Atkinson G, Aubry BS. Problematic Risk Adjustment in National Healthcare Safety Network Measures. Am J Med Qual. June 2019:106286061985907. doi:10.1177/1062860619859073

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The NHSN Standradized Infection Ratio (SIR): A Guide to the SIR.; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/ps-analysis-resources/nhsn-sir-guide.pdf.

- Nerenz DR, Hu J, Waterman B, Jordan J. Weighting of Measures in the Safety of Care Group of the Overall Hospital Quality Star Rating Program: An Alternative Approach. Am J Med Qual. March 2019:1062860619840725. doi:10.1177/1062860619840725