Inside Angle

From 3M Health Information Systems

The Florida Medicaid approach to quality improvement in managed care

One of the fundamental objectives of Medicaid programs contracting out their sizeable budgets to managed care companies is to improve the quality of care for their beneficiaries. As we frequently highlight, low quality care comes with greater cost, not less. And more often than not that cost can be averted with better coordination of care, follow up and engagement.

At a first look there appears to be a simple and obvious alignment of incentives to increase value by avoiding the costs associated with poor quality. This is achieved by providing a capitation rate for plans to manage the health of beneficiaries. The plan is provided with a fixed amount of money to purchase care and provide services on behalf of their enrolled beneficiaries. If they better manage care, then the difference between the capitation payment and utilization costs (medical loss) is greater and they generate profits. If medical loss rises relative to the capitation rate, they generate losses and, most likely, exit the market.

This simple analysis is thwarted by three related complicating factors. First, to better manage care you first need to know where care is deficient. Without any means of comparing their performance, a plan (or at least those employees responsible) struggles to understand this without any benchmark for comparison. Second, reducing utilization to generate that profit requires some investment, an incurrence of upfront costs. If successful, those costs will reduce medical loss and generate a gain—but that same gain may well be eliminated when future capitation rates are established since the observed cost of care upon which those rates are based has fallen. In the world of economists, the incentive is dependent upon the discount factor we place on future profits and the risk of not generating returns to offset the initial costs. You can understand why staying still and not pushing the envelope is an attractive (if perhaps not rational) proposition. Third, adding to that risk of not realizing returns, the upfront costs to reduce medical loss may be wasted on a population notorious for churning both in and out of the Medicaid program and across Medicaid plans. Ultimately, paying through capitated rates is insufficient to stimulate quality gains; achieving those gains requires a little nudge from a supporting policy to gain the attention of those setting plan goals.

Medicaid programs in states such as Texas and New York, and for Medicare Advantage the “Star” Ratings, provide this supporting policy by publishing a set of comparative performance benchmarks for plans to access and by creating financial incentives to control utilization associated with low quality. The support comes through a separate process intended to stimulate change. In this model (and the specifics vary greatly), a performance target is established and plans/providers are given incentive payments to hit quality targets. Quality and rate setting are treated as independent tasks wherein quality evaluation results in a payment adjustment and the quality standard is set by the agency independent of the plan or provider.

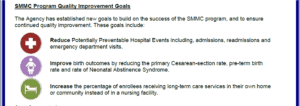

In the latest round of procurement for the Statewide Medicaid Managed Care (SMMC) program, Florida Medicaid has done two new things (or at least things that are new to us). First, they took the step of integrating such things as reducing PPEs (potentially preventable events such as readmissions, hospitalizations, ED visits) that add cost and are correlated with low quality outcomes directly into the capitation rate setting and plan bidding process. This is an explicit recognition of something we all recognize—low quality has a cost and that cost is borne by the Medicaid program through excess utilization baked into capitation rates. Before decrying this as an “efficiency adjustment” layered in exogenously from a black box set of benchmarks, we should clarify that the process of defining the amount of utilization to be targeted for potential elimination was based entirely on Florida experience using data and approaches that had been previously distributed as comparative reporting on the Florida Agency for Healthcare Administration (AHCA) website. But the real novelty is the second component, as part of the bid process plans undertook to reduce potentially preventable events. In other words, plan contracts now contain explicit commitments to achieving measurable targets of utilization reduction set by plans rather than by the agency.

Source: Quality Metrics Program Highlights 10/19/18

Given both 1) the potential for winners to bid low and ask for additional funds later (to avoid the state embarrassment and disruption) and 2) the need to satisfy CMS approval oversight that rates be feasible, the actuaries engaged with Florida (Milliman) had to establish credibility guidelines to help gauge whether bids were overly aggressive or just plain misguided. Unsurprisingly plan bids fell within credibility ranges—plans have a good sense of what can be achieved in utilization reduction when pushed.

At this point we are unclear what happens if the targets established in the contracts are not met. Hypothetically there could be financial penalties (made possible for PPE as their cost may be directly imputed), redirection of enrollment to other plans or some other measure designed to enforce the plan’s commitment to PPE management. It is something we will be following. What we hope is that the new approach to procurement is a success and that managed care can achieve more of its potential to coordinate care, lower costs and improve the quality of care for Medicaid beneficiaries.

At our user conference in April we are lucky enough to have two of the lead Milliman actuaries that worked on the AHCA rate development process run a workshop for us. If you are as intrigued by this new approach to Medicaid rate setting as us, be sure to sign up for their workshop and ask questions!

Richard Fuller, MS, is an economist with 3M Clinical and Economic Research.