Inside Angle

From 3M Health Information Systems

Silver tsunami meets long-term care: A deep dive

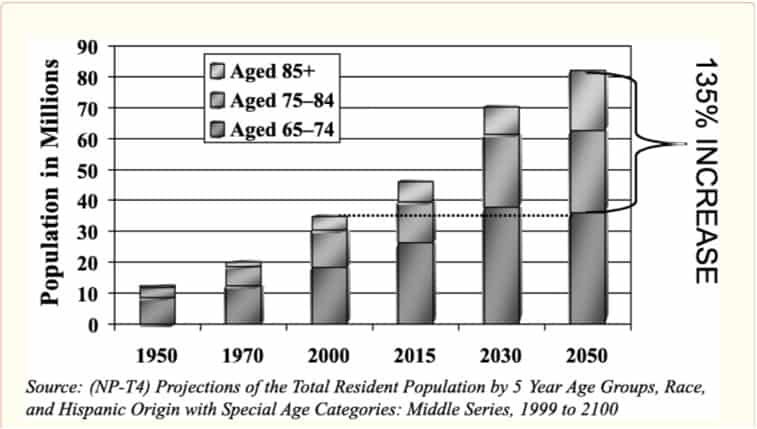

The aging population in the U.S. has been well documented. What is less well understood is the best way to adjust current payment and coverage policies to effectively support and care for our aging population.

Unfortunately, the U.S. has not updated public policy towards long-term care (LTC). According to a recent article:

“The economic burden of aging in 2030 should be no greater than the economic burden associated with raising large numbers of baby boom children in the 1960s. The real challenges of caring for the elderly in 2030 will involve: (1) making sure society develops payment and insurance systems for long-term care that work better than existing ones, (2) taking advantage of advances in medicine and behavioral health to keep the elderly as healthy and active as possible, (3) changing the way society organizes community services so that care is more accessible, and (4) altering the cultural view of aging to make sure all ages are integrated into the fabric of community life.”

“Most elderly who live beyond 75 or 85 years of age become frail at some point and need some form of assistance, making lifetime risks much higher. In fact, 42 percent of people who live to the age of 70 will spend time in a nursing home before they die.”

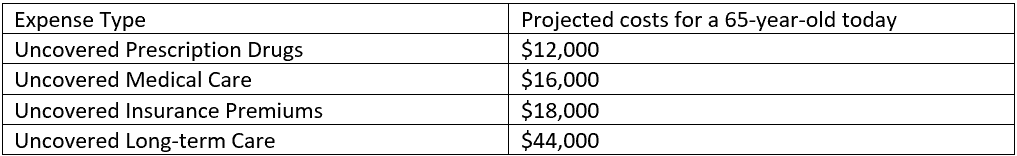

Thus, we are left with a situation in which most middle-class retirees are not prepared for “aging shocks” as documented in the National Institutes of Health article cited above.

Expected Lifetime Costs of Significant “Aging Shocks” for a 65-Year-Old Today

Medicare has documented the expensive and detrimental phenomena of Medicare beneficiaries ping ponging back and forth between nursing homes and hospitals. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has been tracking this issue for some time and notes:

“The Commission tracks three broad categories of SNF quality indicators: risk-adjusted rates of readmission, discharge back to the community, and change in functional status during the SNF stay. We use these measures because they reflect the goals of most beneficiaries: to return home, avoid a rehospitalization, and improve or maintain function. Between 2013 and 2015, the rates of readmissions and discharge to the community improved while the two measures of functional change were essentially unchanged.”

Baby boomers have a range of options available to them, particularly if they have the financial means to pay out of pocket for additional services as they age.

There are some interesting innovations that could be implemented to help alleviate the financial burden of healthcare expenses on our aging senior population including:

- Tax subsidies for unpaid family care givers,

- Apartment living with services among seniors (ex. Bronx, NY The New Jewish Home),

- Medicaid waivers for Foster care for seniors,

- Encouraging immigration of younger workers to provider a care giving work force

- Communities deliberately planning to integrate seniors into the fabric of the community allowing longer healthier aging at home.

The idea of rethinking our view of long-term care for seniors resonates with me. I grew up in a household in which my mother (a nurse and the eldest daughter of Italian heritage) welcomed her parents to live with us for a period, until they became so disabled that she could not safely care for them at home. As a child, I did not understand the life lessons I absorbed from these family members, but looking back as an adult. I can appreciate the richness of those experiences.

Finally, I want to close with some of the encouraging findings from a detailed study on aging:

“Surveys suggest that the 60-year trend of a decreasing number of elderly working has reversed itself as Baby Boomers reconsider their financial needs for retirement as well as how they want to spend more than a third of their adult life. In 2000, the percentage of elderly who worked, nearly 13 percent, was higher than it had been in 20 years (Walsh 2001). The young elderly (people in their 60s) have reported increased ability to work, with a 24 percent drop in the inability to work at this age; the percentage of elderly unable to work at age 65 in 1982 was higher than the percentage unable to work at age 67 in 1993 (Crimmins, Reynolds, and Saito 1999). Most forecasters project this trend to continue as more elderly work longer for economic, social and personal reasons, employers become more flexible and aware of the needs and benefits of older workers, and the labor market remains tight, with a smaller number of available younger workers.”

“Since the sheer size and energy of the Baby Boom generation has led to other dramatic social shifts, some experts see hope that a new imagery for aging is possible. A growing interest in “age integration”—a process that takes advantage of the broadened range of accumulated “life course” experiences in society—has occurred over the last few decades. In an age-integrated society, changes made to bring older people into the mainstream could simultaneously enlarge personal opportunities and relieve many other people who are in their middle years of the work-family “crunch” (Uhlenberg 2000; Riley 1998).”

While there is policy work to do to update long-term care payment policies, there are many reasons to anticipate positive innovations from our aging boomers as they live longer lives in a more active and health-conscious manner.

Gretchen Mills is manager of market strategy for populations and payment solutions at 3M Health Information Systems.