Inside Angle

From 3M Health Information Systems

Access to clinical data and a walker called Rhonda

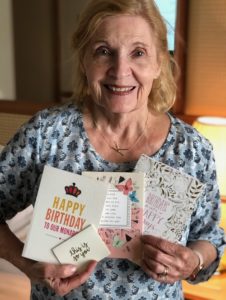

My 83-year-old mother recently returned from a two-month cruise of the South Pacific—Hawaii, Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and more. She’s active and bright and healthy and could easily pass for a woman in her sixties.

But last year was an entirely different story. Suddenly her health began to rapidly decline and she appeared to age as if overnight. She suffered shortness of breath and plummeting energy levels. She passed out several times, once hitting her head on a table edge. A neighbor (who just happened to be a nurse) knocked on the unlocked door when she heard my mother fall and came to help.

After a series of doctor’s visits and tests, we still didn’t know what was wrong. Weeks passed and then a month, while she continued to decline, a little worse each day. She was pale, unsteady on her feet and could barely get around the house. My sister bought Mom a walker, which alarmed all of us—a walker? Our mother? To keep up her spirits (and ours), we nicknamed the walker “Rhonda,” after the Beach Boys song —Help me, Rhonda! Help, help me, Rhonda!

Even with Rhonda the walker, my mother had to stop every few steps to catch her breath. A trip from her bedroom to the kitchen was an ordeal. My sisters, my brother and I took turns staying with her so she was never alone at night. We were mystified by the sudden turn of her health. Was this really the end?

When her primary care doctor couldn’t diagnosis the problem, he focused on a minor respiratory flu that had preceded her sudden decline. He referred her—perhaps too quickly—to a respiratory specialist who apparently stopped looking for other possibilities. But her oxygen levels read normal. Chest x-rays showed some minor but inconclusive anomalies. The specialist mentioned an invasive lung biopsy, but he wasn’t sure it was necessary or advisable in her weakened state. He started talking about “the new normal”—I really can’t stand that expression, by the way—as if simply being in your eighties should be enough explanation. We were getting nowhere. Another month of this and we could lose her.

My sisters weren’t having it. There had to be a cause for our mother’s abrupt decline. They pushed for more tests and another doctor’s opinion. And so, it was during yet another visit with yet another respiratory specialist, the nurse at the clinic overheard my sisters talking and called them over to her desk. The nurse was scrolling through lab tests in Mom’s medical record. “I’m sure you must know about her declining iron levels?” We didn’t. Her iron levels had been slowly, but steadily dropping to dangerous levels for more than a year.

There it was. A crucial data point had been missed. Should we have reviewed Mom’s lab results? Probably. She hadn’t told us that she had taken an oral iron supplement for a while but stopped because it caused severe nausea. But why didn’t these lab results get a doctor’s attention sooner? With all our jumping between doctors and clinics, were there interoperability issues that prevented or made it difficult to access lab results?

Whatever the case, the doctors shifted their focus. A few tests later, an upper endoscopy revealed a gradual bleed from striations in her esophagus, a condition easily treated with medication. But her iron levels still needed to be restored. In her research, one of my sisters discovered and pushed hard for an iron-infusion therapy usually limited to leukemia patients in chemotherapy. We were finally on the right track. Mom received a series of saline and iron infusions that restored her health in a few weeks.

I don’t want to assign blame. Everyone involved was trying to help my mother. But worries about clinical validation and denials can mean crucial treatments sometimes don’t happen if patient documentation is incomplete or overlooked. Computer system interoperability and communications between doctors, referred specialists, hospitals and clinics are at best barely adequate. The increasing administrative burden on physicians causes widespread burnout. Missed data and unintended mistakes are inevitable.

The outcomes for my mother and my friend’s husband were positive, though it haunts me how easily it could have been otherwise. Happily, my mother’s recovery was miraculous and sustainable. In a matter of months, she was cruising the South Pacific. No more need for “Rhonda” the walker. Rhonda sits unused, though not unappreciated or forgotten, in a basement closet.

Steve Cantwell is a senior marketing communications specialist at 3M Health Information Systems.